Josef Kostner

Biography

Archaic Spirits

In observing Joseph Kostner's cement creatures, which invariably seem to be primordial beings, or his faces, which always give you the impression being a non-visage, you cannot fail to immediately see the secret correspondences that are established between sculpture and place, between the deformed and swollen features of the bodies and the immense, chipped blocks of the Dolomites that crown the valley (the Gardena Valley) where the artist was born and where he has lived almost uninterruptedly. It is as if his eyes, in opening up to see the world, had taken in all the ascensional and dark, threatening movements and had turned this sight into the bearer of his sensitivity and factuality. Even psychoanalysis tells us this: "for each of us, our way of looking at things is built through the dynamic relationship we have with what surrounds us".

But it would suffice just to look at the figures shaped by Giacometti, which are always on the point of collapsing and visual consumption: they appear to be affected by a cancer of the being, almost compressed to the point of pain, so that all of their inner nature oozes out of them. Behind that appalling formal ruin, there are mountain landscapes from the childhood of the Swiss artist, Stampa in the Bregaglia Valley, the Jungfrau, the Pale di San Martino, the Gran Sasso, and from behind the enormous bases, the idea of a Cyclopean crash of reliefs emerges, the sensation of an enormous deposit of material from a landslide.

There is also something dark and alarming in Kostner; he models, scrapes and injures his figures until he brings them to a sort of archaic stylization, where the forms are barely rough-hewn or disturbed by irascible deformations. But while Giacometti works through corrosion and the elimination of material, to arrive at an individuality that emerges from the remainder, Kostner works to return almost to the primary physical body of the sculpture, to a plastic essentiality, where all subjectivity still appears to be immersed in the mass of material with which he started. One looks towards the end of the being, the other towards the beginning. One seeks a "statue that withdraws into such a far away and dense night that it is confused with death", while the other, instead, chases the strokes that seem to push themselves towards the outside, towards life and light. But in both cases the artists start from the mountain, from the narrow and dark floors of the valleys, like creeks, to earn themselves a rough penetration of the psychology of human beings.

Can we speak of existentialism in the case of Joseph Kostner's sculpture (as in the case of Giacometti)? The answer can only be affirmative, if by existentialism you mean the abandonment of every metaphysical category, in favour of the accentuation of physical data, of the proposition of the "question of being" (Heidegger).

But then the artist himself stated "I want to represent man, marked by struggles and disappointments". He is not a hero or a Nietzschean superman (even if some fused cement structures could bring that to mind), but a man, fixed in all of his wealth and misery, who has a hard time getting up from the ground or even still appears to be covered with earth, as if he came from inexpressible historical depths, from the Moai monoliths of Easter Island, from the sandstone rocks of Stonehenge or ancient African amulets. But this doesn't mean that Kostner's sculpture intends to draw on the past, to develop a sort of linguistic nostalgia towards archaic forms of expression. There are no citations in his work, no tracing or replicas. His confrontation with stratified images in the culture of the past is a need to draw on the very origins of creativity. It is a need to sound the first gestures of doing and being. The language of Antelami could even be evoked, with his powerful, stylized realism, or Niccolo dell'Arca, full of furious expressive force, or Donatello, with his hard and angular figures, etc: the matter, for Kostner, does not change. All references to the past operate as a platform to better interpret the present (one's manner of being and presence in the world).

For him, sculpture has a figurative and "universal" value, it goes beyond ages, techniques, styles or mediums or, better yet, includes them all. And perhaps that's why his "Humanity" features a remote structure and is not lost in detail that could distract the observer it intends to challenge time, to beat it an its own ground, the ground of durability, resistance and continuity.

Look at Hercules, for example: the figure is entirely closed within itself, closer to the idea of herma than to the idea of human. The bust appears to be buried and closed within a sort of sarcophagus that accompanies its members. It has a rough surface, as it were crumpled up bones in a wrinkled shrine of a body. And if you observe it carefully, you can see how the torso lengthens out (it includes itself and the legs). So Kostner's Hercules is transformed into a demigod, which has definitively lost all dynamism, revealing itself to be half immortal and half dead.

Yet, it is as incorruptible as an ancient and powerful rock, like a fantastic giant. The Ortisei artist is not interested in referring to traditional iconography, but in giving a visage to a myth and a body to a legend.

On the other hand, when we observe the figure “Eva”, we have the sensation of looking at a Mariniana Pomona (since even here, the anatomical details are extremely limited): an essential hint at the hair, two falling breasts, extremely rounded thighs. It is a "ubiquitous" creature because it is in reality and in dreams (or nightmares) and inhabits an outpost, suspended between the past and present, between affability and standoffishness. It is ambiguous, because you wouldn't know how to define it, except as a "suspended enigma": it is within us and beyond us, ancient and at once very modern. It is inhabited by deformity, it presses forth from inside: its shape has arisen from a dark bottom, appearing in the light as a sort of exudation or tumescence.

Kostner's objective is to shape a maternal figure, but he does it with a gesture that "stops" inside the material. So, the excavation, the intaglio and the cutting are part of the figure, and the image, in the end, is seen as a scar and an amulet, as a spasm of matter and an ancestral idol.

If we then observe works like the sitting figure “Riposo” or “Attesa”, we seem to be looking no longer at figures but at states of being or, at least, at dimensions in which the being wraps around things and is confused with them. They are bony works, full, corporeal, in which the bodies have emptied features, however, like totenmasken metaphysical manikins. They appear to be formally strong sedimentations, impregnated with material, but also as structures where the material is decomposed and melts, like wax near a source of heat. It is magma, delivered to existence in the flow of aggregation and lost rivulets.

So more than an idea of anatomy, we are led to conceive an idea of passage, of multiplication of "free limbs".

Finally, if we look at the heads (various versions that he proposed), which recall the series of Jeanette by Matisse, we have the sensation that the artist took some absolutely audacious liberties with respect to the previous plastic solutions. There is no more brutalism or barbarous models, but the development of a linear chain of events, based on the multiplication of roundness. Every expressive research gives way to a plurality of elementary volumes. The physiognomy is no longer altered, but we see a playful dialogue of additions and subtractions, until we come to a hypothetical, abstract visage, which may belong to all of them and to none.

Kostner's hand is always oriented towards giving a primitive aspect to his sculpture. But he knows very well that basing the sculpture on a model means regressing to rhetoric or academic work, making the purity and originality turbid. It is not important if this model is based on ungrammatical features, approximations and disorderliness.

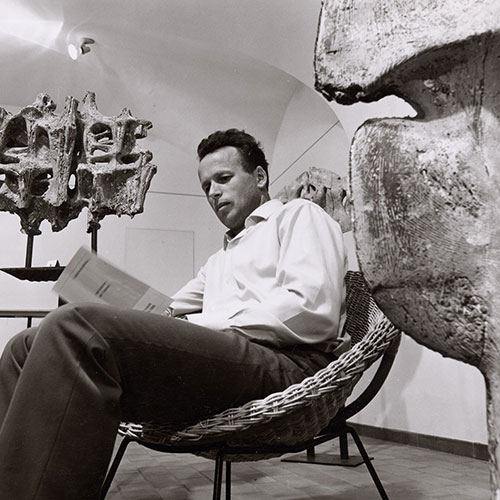

Simplicity and primitive rigidity are not assumed by the Ortisei artist as a stylistic element or cliché: his formal simplicity is also structural solidity; his compositional humility is also dramatic energy. It's as if each of his works were a passion, an immediacy, a spontaneity that crosses over the apparently summary nature of the figurative traits, but the "roughness effect", above all, is more of an ethical element (a tie with the mountains and their roughness), which is an aesthetic fact (formal research, rigorously conceived and well performed). The artist himself stated: "My ambition is to be inspired and surprised by emotions and until reach a truly surprising result, I prefer to destroy everything and start a work over". But, in the end, this is also the thought of the art historian Lionello Venturi: "The primitive gesture - he wrote is not a lack of taste, nor is it a negation or a passiveness. It is an assertion and an activity". And Kostner understands this thoroughly after his visit to Henry Moore's studio (in the early Seventies): he understood it, observing the works with emotion-evoking empty spaces, limbs marked by upward tension, corpulent figures whose empty spaces lead to warm obscurity. He understood the need to identify unconscious impulses with an "objective correlate”, with an external symbol in durable material. He understood that the power of the expression is more important than the beauty of the shapes.

"Beauty - said Moore - tends to please the senses, expression possesses spiritual vitality, which for me is more moving and goes deeper than the senses“.

Anchored to a millenary memory of history and art, Kostner's sculpture may fundamentally appear to be a figurative sculpture (although some solutions are devoid of any objective reference): but it is always a figurative expression to be understood more as a concept than as a theme. In fact, every shape, albeit drenched in pregnant reality, is not verist. It does not illustrate. It does not recount or explain, but simply "is". It is the shape of an image visualized with violent certainty in structures, volumes and rhythms.

It is precisely due to this continuous process of interdependence between the shapes of life and the life of shapes that it can be said that Kostner, who embodies and transforms his existence in his work, day by day, has thought, imagined with suffered and contested through shapes.

He never believed in experimentalism for its own sake, remaining fundamentally a traditional artist, tied to the profession and the hard work of doing, like an ancient master. But again here it is de rigueur to specify that the tradition has never deteriorated into tired traditionalism, or much less into restoration. He remains outside any recovery or revival, although to gather all the implications of his work, we can mention the sculpture of the Palaeolithic age and ancient Greece, Etruscan, Romanesque, Gothic, Black, Indian sculpture, etc. That is to say that every reference ends up as testimony of a fundamental idea of humanity, if not of the cosmos. And even resorting to formal exasperation and emphasis of somatic traits can be read in this direction. Namely, as an attempt to break the seal on every established idea, closure or fixation, to arrive at the heart of things and individuals. Kostner seems to adopt the words of Michel Serres "It is important to break the fetish, open the cadaver, operate on it”; it is important to touch, to make even the most oppressive volumes tremble and jolt (perhaps mixing cement and pigments, so that they express what is not said, if not the unspeakable.

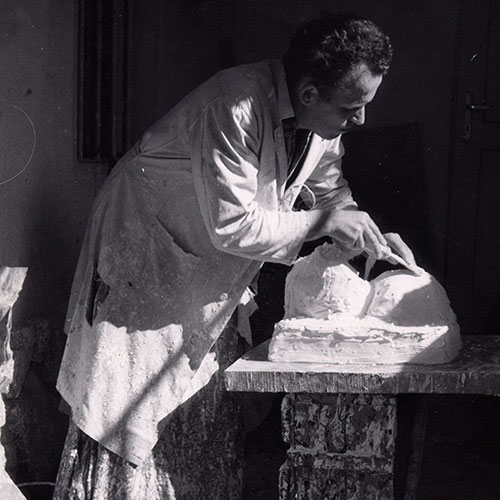

The initial use of wood was often remembered by the artist himself with negligible enthusiasm (“for many years my expression dealt with the trunk of a tree, which gave nothing to and received nothing from"): he felt it too tied to a typical tourist production in Val Gardena (with nativity scenes and votive statues) and so he began to use clay, inasmuch as it is a material that posed no limits to his inventiveness and, in the end, experimented with the poor material of cement, which had been passed through alchemical processing (that sound like foundry work) and coloured in various ways, so that the image took on a caked and swollen "vestment".

Perhaps Kostner would have liked to perform with Arturo Martini in one of his restless commandments, metaphorically suggested to sculpture: namely "please let me not be a pyramid, but an hourglass, so that I may be overturned; let me not be a weight but a scale; let me not remain in three dimensions, where death hides" in other words, let my static nature also be a motion, allow my fullness to understand emptiness, time to go by in my presence. But which time? Of course, the past with all of its fund of memories, values, evocations; but also, the present, understood as the moment when every element runs within every other, when the world appears to be extremely full, full to the brim, abounding with things, in which reality gives of itself only in fragments, dross, ruins. Like reading that "Column" made up of superimposed architectural relics and elements that writhe on the ground, like germinal and energetic forms or even the "Maternity", where the bodies melt and liquefy, becoming confused with other objects?

The relationship between things is immediate and direct: no distinct boundaries or limits have been developed. It is today's horizon: the horizon of a language that is not spoken, nor is it hidden, but it is hinted at. Kostner attempts to gather the fragile balances, he is immersed in the accidental and ephemeral, but always to glean slow and imposing "movements". And it couldn't be otherwise for an artist who asserts: "matter possesses me. I feel it. Matter and I are one".

The emotion of the sign

In dealing with the graphic side of Josef Kastner's work, we have to immediately clear the field of a series of preliminary misunderstandings and ambiguities. One of them concerns the all too drastic distinction we tend to make between sculptural practice (understood as the greatest possible degree of materiality) and drawing (understood, on the other hand, as the denial of materiality and the triumph of immateriality). The other concerns the tendency to consider drawing as a marginal experience, set aside, almost intimate in the presence of the plastic fact, which is always exhibited and spectacular (even when it is performed under the sign of the fragment, of the fracture, of the wound, as it is in the case of Kostner). Yet another is thinking of the sheet of paper as the mere place of a planning event, realized with a view to and as a function of the sculpture itself.

The interminable sequence of drawings that Kostner has achieved, starting from the Sixties, has so many and such technical articulations and formal modulations as to make it natural to think that they were the original signs of the work, the visualization of the ideas as they were initially formed. And that they are therefore not mere tools of support or study, but rather pages of notes, small yearnings of "writing”, like the notes in a diary; never just theoretical experiences or inarticulate and mechanical preparatory materials, but rather visual disclosures of the work "in progress" - suggestions that may come from the simple observation of a root, a leaf or a stone. "Anything can become a source of inspiration when you are hiking around the mountains", notes the artist himself, any natural element can become something that excites your imagination. And it's not hard to believe those who speak of Kostner's hectic pace of work, his obsessive and rapid noting down of "abstract things" and "hieratic figures". It is testimony of an inner desire to chase life in its incomprehensible changes, sudden pauses and unexpected revelations.

But the two creative moments of drawing and sculpture must not be taken apart in a defining manner. One is founded on immediacy, on the here and now (typical of graphic activity) and the other is based on slow execution, on a procedure that requires time (shaping the clay, covering it with chalk, emptying the mold and filling the cavity with cement); one is identified with an impulsive dimension, while the other is developed through meditated gestures, regulated by precise techniques, one moves towards open, hypothetical results, carried out first with imagination and then with the hands, while the other is real and certain (albeit etched by continuous indecisiveness and agony). In the end, the two moments have a somewhat parallel nature, of mutual influences and secret consonances.

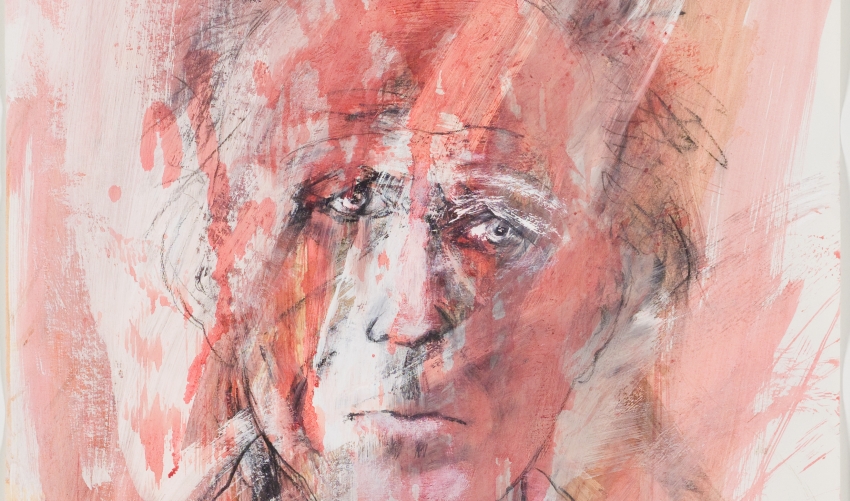

Thus, the first graphic experiences realized with an ink pen have an uninterrupted action. They are never truly finished and can always be taken up again, duplicated and altered. We are speaking mostly of female figures, pushed to the limit with a few strakes, destroyed almost from the inside, overturned, desecrated (like only a De Kooning knew how to do). In any case, these initial sheets contain the anguish of the white page and everything gives the impression of leavening: the signs, the deformations, even the timid traces of red that seem to cover the skeleton of the figure. And you don't have to look far to find the plastic "pendants", because there are innumerable "weaknesses", "disorders of the flesh", contortions and openings in the cement.

With the advent of the Seventies the pagination of the drawing took on greater formal structure. The page was divided into blocks (or windows) where individual figures or pairs of figures are exhibited. The scenario takes on the traits of a story or a sequence, like the ones that can be seen in some gothic church frescoes. But there is never an authentic progression of events or continuity in the narration. Every frame stands alone, like a still photogram. The bodies (and the frames that contain them) are dealt, however, with a greater degree of attention, "written and rewritten", with a colour that thickens until it suggests an idea of architecture (of an aedicule, or a niche), without abandoning the abrasive and cancelling effects that are also typical of many of Kostner's sculptures (suggesting both the censure of the finished image and its multiplication of levels, boundaries and visual revelations). In some graphic works the frames actually interact with each other, creating a sensation of overcrowding, movement and theatrical frenzy. And the fact that the shades are almost casually splashed on and the colour (almost always water colour) is applied with cloths and sponges, preventing any form of control or rule, suggests that we are not far from the performing arts. We are no longer confronting a vestment or a wall, but rather a self-assured, audacious, carnal blot, inasmuch as it neither hints at nor follows the various bodies, but penetrates and invades them, accentuating their gestural exasperation and formal exuberance.

Only after his visit to Henry Moore's studio (in the early Seventies) do we see an extremely thick weft of inks, which brings a large and solemn representation to the forefront, like prehistoric dolmen and menhir Like Moore, Kostner's space stops being an abstract entity and becomes an experience, where vicinity and distance, horizon and imminence, vision and con tact all became one. It's like what happens in some of his gigantic and hypertrophic sculptures. These drawings also lose any possibility of rationalization, freeing a primitive element, an original and eternal relationship between Nature and humanity. Every sign that "describes" a living being is also an echo of the existence of fossil, vegetable and biological nature. We could say it with Oscar Wilde, that things stand before the artist with or without a name, and although they stand alone, they feel all things vibrating within themselves”. It is the piercing gaze, like memory or repetition, like resonance. Nothing is disassociating here; on the contrary, everything is characterized by the attempt to convey a deep sense of cosmic unity. The universe of these drawings is the narration of what has been heard and listened to. It is the representation of what the hands have brushed against and touched, the trace of what the eyes have surprised and observed. So objects become the life of the subject and the author becomes the truth of objects that penetrate the heart.

Over the course of time, the various figures initiate a dialogue with the other elements of reality and the imagination: with tables, chairs and thrones, thus creating a plurality of relationships, a universe that thickens with symbols and swarms with signs. And although on one hand a sort of paralysis and visual immobility is emphasized, on the other hand the suspended relationship between things leads the knowledge of the things themselves to go beyond their empirical entity. Even more so because the figures and objects are not created with a sharp and immediate stroke, but through an authentic weft of signs that make them vibrate in space. Often, traces of existence are spread around everywhere, like ghosts or double figures, conferring the composition with the idea of being incomplete and having an open result, based on conjecture, which is in perpetual transformation - a bit like what happens in sculpture, that appears as a delirium of volumes and masses of material that collapse over each other (one inside the other). But the same can be said when, during the course of recent years, a single being (or a single visage) occupied the scene: everything is again openness and precipice, an abyss and ecstasy. The vision is no longer unitary, but is fragmented instead, dismembered with reds and blues that accentuate the idea of collapse and disaggregation. Kostner is invariably interested in the sense of swooning, of abandonment and bewilderment. His ecstasy lies in loss, in waste and dispersion.

Yet the image never falls into formlessness or amorphousness. The fury that sometimes commandeers Kostner's drawing is dictated by the need to retain a wizard-like relationship with the metamorphic potential of the shapes. He is convinced that no line can ever definitively close up the image, because this would mean to petrify it. The line must remain alive and fickle, instead, capable of breaking, being cancelled or starting up again at any time. And no matter if it refers to metallic purity or an unruly and allusive doodle; it must be capable of narrating without resolving any enigma - it must invent spectacles that have only emotion- al (and never realistic) references. This is what the artist has always sought in the torrential abundance of his sheets: namely, to convey a transfigured daily life, where the images mime a "commedia dell'arte" in a terribly hauteur, which is transformed into a disquieting "human comedy" without our becoming aware of it.

Luigi Meneghelli